How to Write a Picture Book

I’m sharing how I’ve learned to write picture books through taking Storyteller Academy classes. I’ve been having an email conversation with a good friend (who also happens to be an award-winning picture book author) who’s having doubts about whether or not she’ll ever write another book that sells. I’m sure that she will. We all have times when we question ourselves. You just have to keep doing the work.

But what is the work? Sometimes, you’re not even sure where to start. Or you get stuck in the messy middle and give up. Whether you’re new to writing picture books, or you’re just feeling stuck, I’m hoping this step-by-step post is a virtual hug that will help you find your story.

1. Develop a Great Picture Book Idea!

This is the most important step. Having a great idea will make everything (writing, querying, submitting, marketing) going forward so much easier. You want to come up with a great concept before you put in all of that work. Why will people buy your book? Why will kids want to read your book? Why will teachers and librarians need your book? If you could only write a few books in your lifetime, which ones would you write?

Arree Chung teaches that a great picture book has three things. It’s emotionally strong, kid-relatable, and appealing (has It-factor).

But maybe coming up with a great idea is too much pressure. In our Submission Ready class, Melissa Manlove challenged students to come up with lots of bad ideas. She said, “Your brain is a machine built to make ideas, and the way you use it is the way it learns to be used. So, the more ideas you try to come up with, the more your brain will come up with ideas.” When I tried this, it worked! It worked so well that I had to turn it off to focus on writing and revising my stories, haha.

And after sharing some of her favorite picture books that she’s edited, books that originally sounded like terrible ideas, Melissa said this: “You want to write down all of your bad ideas, all of the ideas that seem like real long shots, the ideas that challenge you, the ideas that you just don’t know what to do with yet, because some of the real magic of the creative process is right there in the journey between something terrible and something amazing.”

So, if you’re stuck, just write down ideas. You may have already done this during Tara Lazar’s Storystorm challenge at the beginning of the year.

Once you’ve generated a lot of ideas, you’re going to wonder which one to write. Go back up to the first paragraph in this section, and ask the questions I listed there. Read picture books in bookstores. Ask a bookseller in the store which picture books are selling.

Ariel Richardson, who also teaches Submission Ready, suggested you ask the following questions:

- Which one really speaks to who you are and what you’re passionate about?

- Which ideas are kid-friendly, kid-relatable, will get past the gatekeepers, and might tie in with curriculum?

- Which idea is fresh enough to stand out in the marketplace?

And once you’ve selected your idea, you’re ready to . . .

2. Turn Your Idea Into a Picture Book!

Picture books are structured differently than short stories and novels because pictures tell at least half of the story. Page turns matter! If you aren’t the illustrator, you have to leave room for the illustrator’s part of the story. And you have to make sure you’re giving the illustrator something interesting to work with on every page. I had so many “Aha!” moments when I made my first dummy in Arree’s class a couple of years ago.

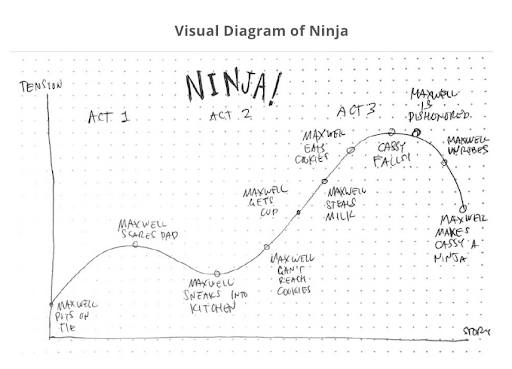

But in other ways, picture books are structured like any other story. They’re usually organized into a three-act or triangular structure.

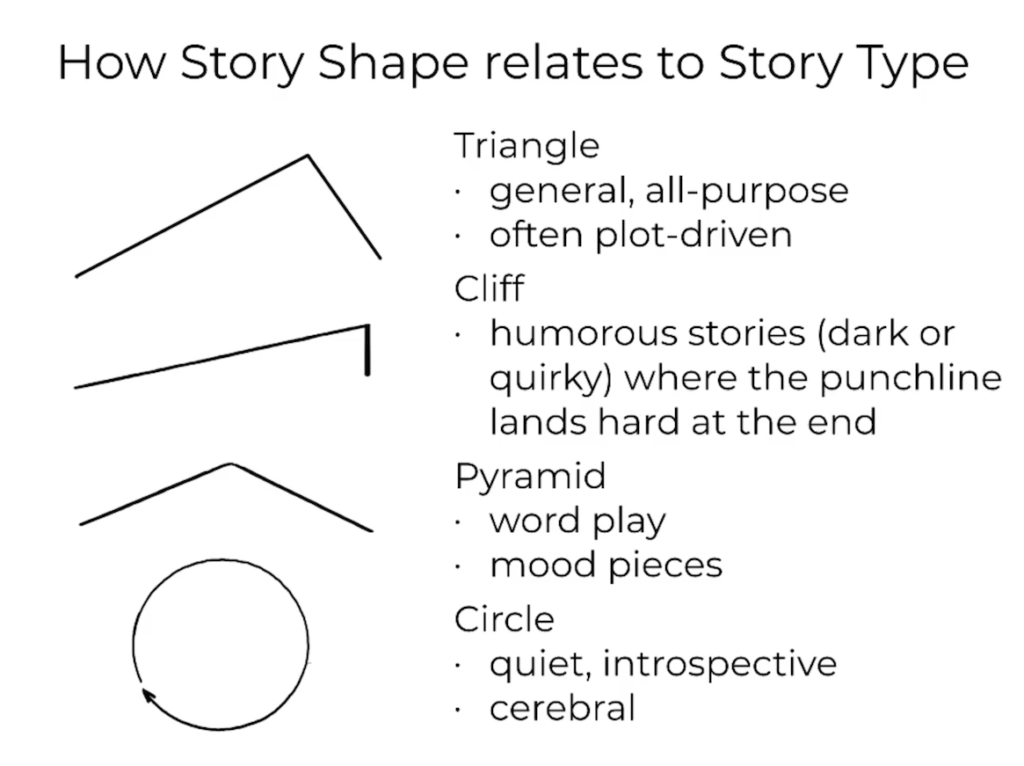

In his Writing Picture Book Manuscripts class, Jim Averbeck teaches different picture book story shapes that work (and shapes that don’t work).

In his Writing Picture Book Manuscripts class, Jim Averbeck teaches different picture book story shapes that work (and shapes that don’t work).

There’s more than one way to come at a picture book. Personally, I start out by writing the first draft. I know it isn’t going to be pretty the first time, but I’m more of a pantser (writing by the seat of my pants) than a plotter (someone who plans out the story). I like to have a story draft to work with. Even if I end up tossing it and starting over, I’ve learned one way that I’m not going to write my story idea.

In Submission Ready, Ariel and Melissa actually had us choose three of our bad ideas to turn into good stories, so we wrote three first drafts in a week. Of those three, I only loved one enough to keep working with it. I may still go back to those story ideas, but the drafts I wrote didn’t grab me.

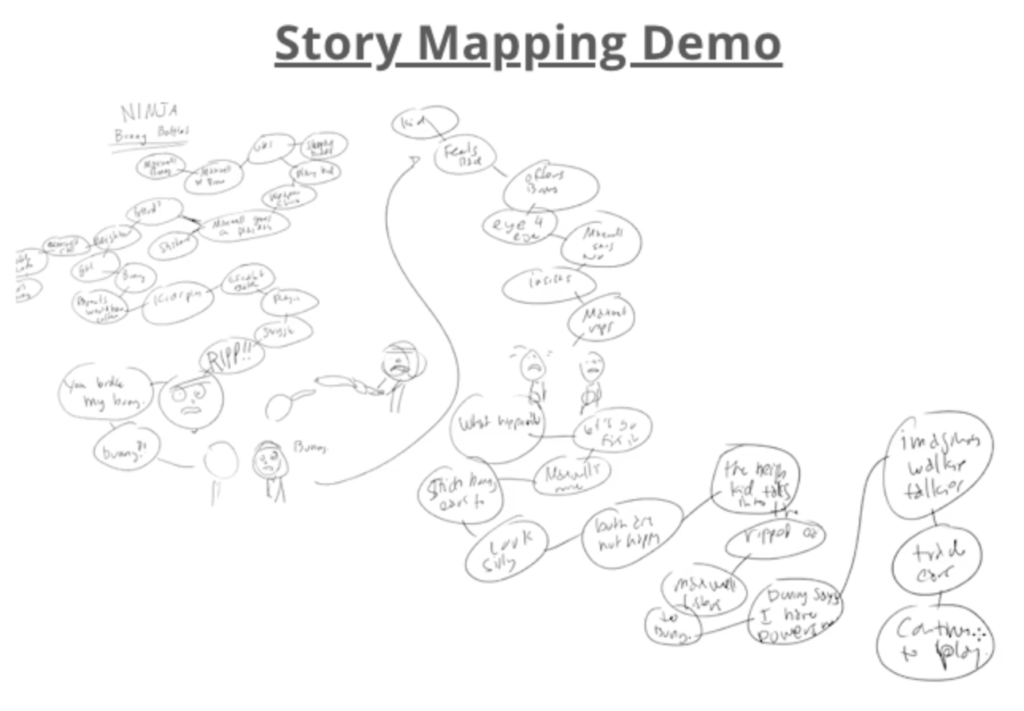

If you’re more of a plotter, Arree has a story mapping exercise. I use it more after the first draft to organize my revision, but it’s also great for exploring your story’s possibilities before you write it.

Make sure you can identify all of the following elements in your story:

- Characters

- Setting

- Problem

- Inciting Incident

- Escalation

- Resolution

- Hook/Concept

Once you have your story, you can . . .

3. Find the Heart of Your Story!

Your story has a heart, and you don’t want to accidentally cut it out when you start revising.

- What do you want your reader to feel? Identify the core emotion of your story.

- How can you escalate the story problem (which you identified in the last step) through escalating that core emotion?

- As you read through your story, what are the magical moments? Arree has students identify and draw magical moments.

Once you have those magical moments—and your story’s heart—safely secured, you’re ready to . . .

4. Check Out Mentor Texts!

You’ll want to read a lot of picture books: books with the same story shape, books with similar characters, books with the same theme, books written in a similar style. If you wrote a rhyming picture book, for example, you’ll want to study picture books with the same rhyme schemes and meter that you’ve written yours in. (If you’re not sure what meter is, you’ll need to take a class on that or rewrite your picture book in prose. Writing a rhyming picture book with outstanding meter—which you’ll need to sell it—and interesting rhyme is much harder than writing a picture book in prose.)

Librarians are your new best friends. Ask them which picture books are most popular, which picture books fit into the categories I listed above, and which are their favorites.

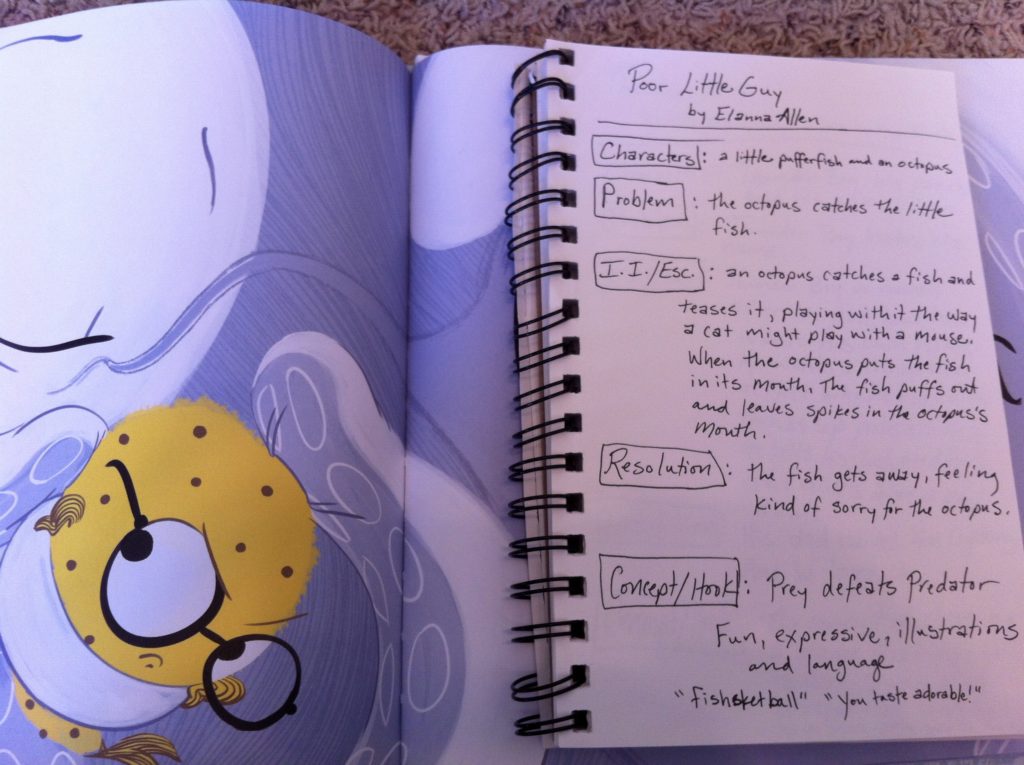

Arree has a Master Studies exercise that will help you find the elements of story in the picture books you're reading. As you're reading, identify the same elements that your story should have:

- Characters

- Setting

- Problem

- Inciting Incident

- Escalation

- Resolution

- Hook/Concept

Once you have your mentor texts, you’re ready to . . .

5. Revise Your Picture Book!

This will probably be the longest, hardest step in writing your picture book, but I’m going to share some tools that I wish I’d had in the beginning. Plan on going through multiple revisions. And get feedback from people who understand how the picture book industry works: critique partners (other picture book writers and illustrators), mentors, agents and editors at SCBWI conferences.

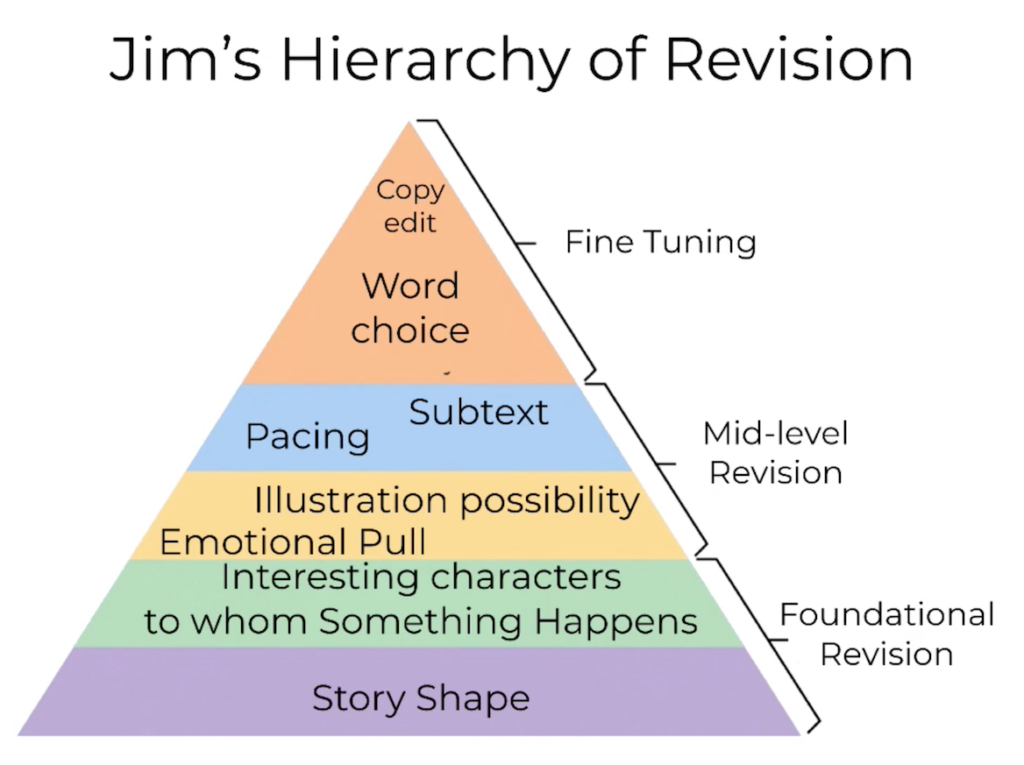

Jim Averbeck’s Hierarchy of Revision is just plain fabulous. Start at the bottom and work your way up.

Writers: Make a dummy of your manuscript. It will help you cut unnecessary description and pace your story better. You don’t need anything fancy. Copy paper and a pen works for me. You don’t need to be able to draw well. The pictures are for you, and you don’t have to show the dummy to anyone else. If you do want to share the dummy with your critique group, the Genius Scan app makes it quick and easy to turn your dummy into a shareable PDF.

Keep revising and getting feedback on your revisions until the feedback you hear (from a trusted source) is that your picture book is ready for submission.

And that’s how you write a picture book.

If you have questions or advice, please comment below. Thanks for reading!

Blog Contributors

Myrna Foster writes and edits content for Storyteller Academy and the WriteRiders Newsletter for SCBWI Nevada. She has spent a lot of time teaching and coaching children, including five years as a preschool teacher. She's also worked as a journalist, and Highlights High Five has published six of her poems.

Arree Chung is an author/illustrator and the founder of Storyteller Academy. Arree’s Ninja! series has received starred reviews from Kirkus and School Library Journal. Kirkus also gave a starred review to Mixed, which recently won the FCGB award.

Today Arree lives a creative life, making stories for children. Arree spends most of his time making picture books, writing middle grade novels, and sharing his love for art, design, and storytelling with kids and dreamers everywhere.